Leash reactivity in dogs: Essential guide to causes and solutions

If your dog barks, lunges, or growls on leash, you are not alone. Leash reactivity in dogs is one of the most common challenges guardians face. It can feel stressful, frustrating, and even embarrassing. But reactivity is not a sign of a “bad dog.” Reactivity is your dog’s way of saying they are struggling with big feelings while on leash.

The encouraging part is that there are kind and effective ways to help. With patience, structure, and science-based training, socially sensitive dogs can learn calmer responses and guardians can start enjoying walks again.

Quick takeaways

- Leash reactivity in dogs is caused by emotions like fear, frustration, or over-excitement, not dominance.

- Punishment often makes reactivity worse by adding fear or stress.

- Training that uses positive reinforcement helps dogs build confidence and learn better coping skills.

What leash reactivity in dogs looks like

Leash reactivity in dogs doesn’t have a single “look.” It can show up as barking, growling, lunging, or whining, but also as stiffening, crouching, or even lying flat on the ground. Some dogs overreact because they’re afraid, others because they’re frustrated and desperate to greet.

The common thread is intensity. A socially sensitive dog has a big emotional response to a trigger, whether it’s another dog, a person, a bike, or even a sound. But not every reactive dog looks like the stereotype of a barking, lunging whirlwind.

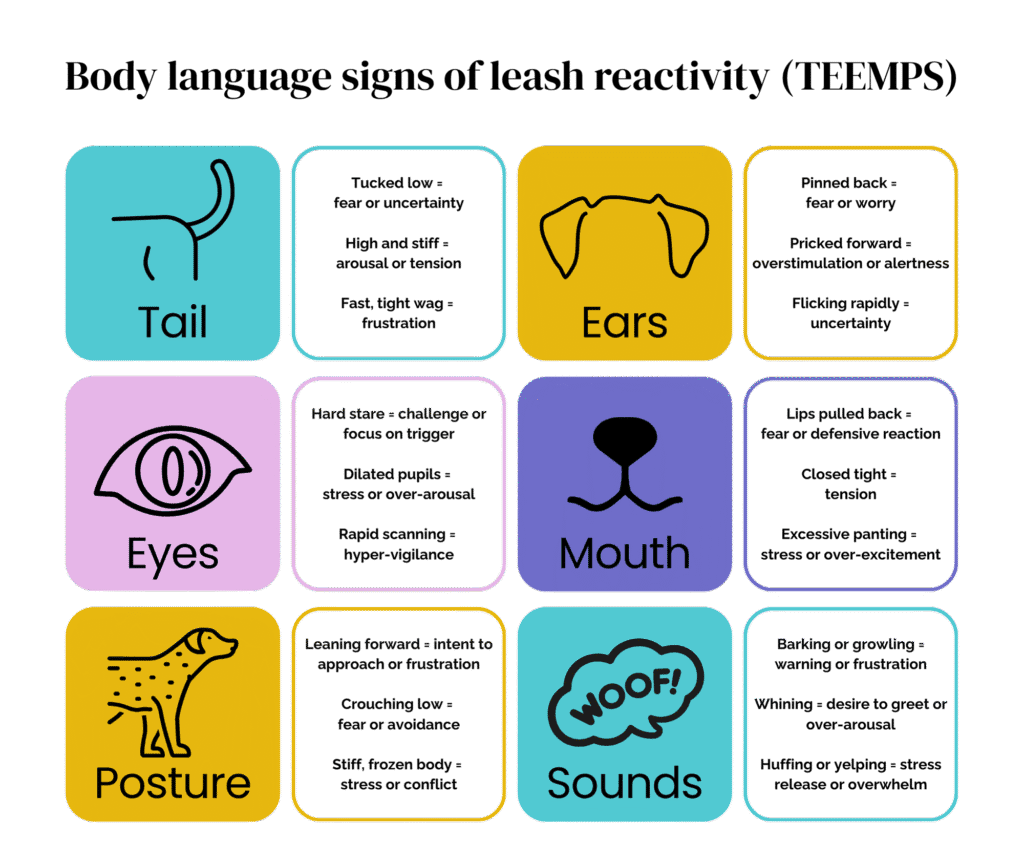

Dogs speak through body language, and noticing these signals can help you understand when your dog is starting to feel stressed or overwhelmed.

Remember: Always look at clusters of signals, not just one. A single cue, like dilated pupils, can have different causes — low light, excitement, or stress. When you read several signs together, you get a clearer picture of how your dog is really feeling.

- Tail

High and stiff if aroused, tucked if scared, wagging fast with tension if frustrated. - Ears

Pinned back when fearful, pricked forward when overstimulated. - Eyes

Hard stare, dilated pupils, or rapid scanning of the environment. - Mouth

Lips pulled back in fear, closed tightly when tense, excessive panting when stressed or over-excited. - Posture

Leaning forward, stiffening, crouching, or even lying flat to “lock on” to another dog. - Sounds

Barking, whining, yelping, huffing, or low growls.

Leash reactivity in dogs can come from fear, from frustration, or simply from being overwhelmed. A dog who is afraid might pull back or tuck their tail while barking. A frustrated dog might lean forward with their ears and tail stiffly up. An over-excited dog might be vocal and bouncy, desperate to get closer.

Not all reactivity looks “big.” Even quiet behaviours like freezing, licking lips, or avoiding eye contact are signs a dog is struggling. The important part is to recognize these signals as a cry for help, not as stubbornness or misbehaviour.

Why leash reactivity in dogs happens

Reactivity is emotional at its core. When dogs are on leash, they lose the freedom to approach or move away at their own pace. That loss of choice can make the world feel more stressful and harder to handle. Many dogs react to cope with that pressure.

Fear-based reactivity

Some dogs react because they feel unsafe. They may bark, growl, or lunge to create space from a person, dog, or noisy object. Fearful reactivity is not aggression, it is an attempt at self-protection. And when the scary thing leaves, the dog feels that their reaction worked, which makes them more likely to repeat it.

Frustration-based reactivity

Other dogs react because they want to greet. They may whine, hop, or bark while pulling forward. A dog who is friendly can look aggressive when their frustration builds up. The leash keeps them from what they want, and the bottled up energy bursts out in loud, messy behaviour.

Over-excitement

Many dogs get carried away by everything happening around them. Too many sights, smells, and movements can overwhelm their ability to focus. Over-excited dogs are not being difficult, they just need help learning how to settle.

Shyness or sensitivity

Some dogs are naturally cautious. They may be startled by a new object or an unfamiliar sound. On leash, they cannot retreat to create space, so even a mild trigger can feel like too much. Reactivity for shy dogs is often about trying to find safety when they feel exposed. Gentle, confidence-building practice helps these dogs feel more secure.

Genetics, environment, and early life

Certain breeds are more sensitive to the world around them. Herding dogs may react strongly to movement. Guardian breeds may be more alert to strangers. Puppies who missed key socialization periods, or dogs who spent much of their early life isolated in a crate, may also find the outside world overwhelming. Early experiences matter, but improvement is always possible with the right support.

Chronic stress and lack of outlets

Reactivity is more likely when a dog is already carrying stress. Dogs who spend hours patrolling windows, barking at passersby, or who do not get enough exercise and enrichment, bring that stress into their walks. Think of stress like a bucket that fills up little by little. When it is full, even small triggers can cause it to spill over. Enrichment like sniffing walks, puzzle toys, and training games helps empty the bucket and gives dogs more room to cope calmly.

Common mistakes that make leash reactivity in dogs worse

It’s natural to feel frustrated when your dog explodes on leash. But some common responses can actually make the problem worse instead of better.

- Punishment

Yelling, jerking the leash, or using shock or prong collars adds fear and pain. Research shows these methods increase aggression and anxiety. - Tightening the leash

Pulling back creates tension and restraint, which the dog begins to associate with the trigger. - Flooding

Forcing dogs into busy environments before they’re ready overwhelms them and makes things harder, not easier. - Avoidance

Walking only at odd hours or avoiding walks altogether may feel safer, but it prevents dogs from building skills. Strategic management is different from avoidance. Management sets the dog up for success while still allowing safe learning opportunities. - Labelling

Calling dogs “bad,” “stubborn,” or “dominant” dismisses the emotions that drive reactivity.

These mistakes not only stall progress, they also increase stress, which makes leash reactivity in dogs harder to resolve.

Why flooding deserves special attention

Flooding happens when a dog is pushed straight into a situation that feels overwhelming. A classic example is taking a reactive dog right into a crowded park or forcing them to remain close to another dog when they are already barking and lunging. To us it might look like exposure, but to the dog it feels like being trapped.

The idea behind flooding comes from psychology. The theory is that if the individual is exposed to the feared stimulus long enough without escape, the fear will eventually fade. This approach has been used in human therapies, where the person can understand the process and consent to it. Dogs do not have that option.

Flooding often makes fear and reactivity worse because:

- The dog’s stress hormones spike and can take days to return to normal

- Instead of learning “this is safe,” the dog learns “this is inescapable”

- The dog never gets to practice calm behaviour

- Dogs cannot rationalize the way humans can, so they do not understand why they are being held in place

- The guardian’s bond with the dog can be damaged, as the dog feels unsafe in their care

You might see a dog stop barking or struggling after being flooded. This is not success. What looks like calm is often shutdown. In behavioural science this is known as learned helplessness, where the dog gives up because they feel there is no way out. A shut down dog is not coping, they are overwhelmed and stressed. You can read more about learned helplessness and the role of choice in training in our article Dog training and agency: Why choice matters.

Modern training takes a very different approach. The opposite of flooding is working below threshold — giving the dog enough distance that they can notice a trigger and still feel safe enough to learn. By pairing those moments with positive reinforcement, you help your dog build new associations without overwhelming them.

The science of helping a reactive dog

Helping a socially sensitive dog is not just about stopping unwanted behaviour. Real progress comes from changing how the dog feels and what the dog does. This is where learning theory, thoughtful management, and structured practice come together.

Conditioning and learning new associations

Dogs learn in two important ways: through associations and through consequences.

Classical conditioning is about associations. A reactive dog might bark at another dog because their past experiences have taught them “dog = danger.” With training, we can flip that meaning. If every time your dog sees a trigger they get something wonderful, like a piece of chicken, their brain starts to connect “dog = reward.” Over time, the emotional response shifts from fear or frustration to anticipation of something good.

Operant conditioning is about consequences. A behaviour followed by something rewarding is more likely to happen again. When a dog looks calmly at another dog and you mark and reward that moment, they learn “calm behaviour = reward.”

The two processes work hand in hand. Changing how the dog feels makes it possible for them to try new behaviours, and rewarding the right behaviours helps those new patterns stick. This is why techniques like marker training, counterconditioning, and games such as “Look at That” are so effective for leash reactivity in dogs.

Timing and thresholds

One of the most important pieces of science-based training is meeting the dog where they are. That means paying attention to thresholds. A dog learns best at a distance where they can notice the trigger but still stay calm enough to think. Too close, and they tip into barking or lunging. Too far, and the learning opportunity may not register.

Timing also matters. Rewards need to come right after the behaviour you want, so the dog makes the correct connection. Even a few seconds of delay can mean the dog links the reward to barking or pulling instead of the calm moment you were trying to capture.

Structure and predictability

Reactive dogs often do better when life feels predictable. That is where pattern games and impulse control exercises come in. These simple, structured activities give dogs a framework they can rely on.

Games like 1-2-3 walking or Up/Down give the dog a rhythm to follow on leash. Waiting politely at a door or practicing “leave it” builds frustration tolerance. Structure reduces chaos, and chaos is what fuels reactivity. By practicing these games, dogs learn that calm choices are safe and rewarding.

Enrichment and outlets

Reactivity is more intense when a dog’s stress bucket is already full. Dogs who have daily outlets for their energy and curiosity handle triggers more calmly. Enrichment can be as simple as a sniff-heavy walk, a puzzle toy, or a digging box in the yard. Mental stimulation matters just as much as physical exercise.

Adding variety to enrichment helps too. Scatter feeding, scent games, or teaching a new trick all give the dog a chance to practice problem-solving. A brain that has healthy outlets for stress has more room to stay regulated in difficult moments.

Stress recovery curves

Dogs, like people, have stress recovery curves. After a stressful event, the body takes time to return to baseline. Stress hormones such as cortisol do not disappear right away and can linger for hours or even days. If stressful events pile up before a dog has recovered, they stay in a state of high alert. This explains why a reactive dog may seem more on edge for days after a tough walk.

We can support recovery by:

- Planning decompression walks in quiet, low-stimulus areas

- Providing enrichment at home, such as puzzle toys or sniffing games

- Protecting rest and sleep, which are essential for emotional regulation

Recovery is not a bonus, it is part of the training plan.

Recovery and decompression as training tools

Rest and decompression are not time off from training. They are the foundation that makes learning possible. Without recovery, the dog’s nervous system cannot process what they have practiced. By building in rest days and quiet activities, we give dogs the space they need to consolidate new skills and return ready to learn again.

The role of consistency

Training does not happen in a vacuum. Dogs learn through every interaction with their guardians, which means consistency is critical. If one person rewards calm behaviour while another tightens the leash or reacts with frustration, the dog receives mixed messages.

Consistency across all family members speeds up progress because the dog knows exactly what to expect. Clear, predictable communication reduces confusion and creates a more stable emotional environment. When everyone is on the same page, the dog gains confidence faster and the results last longer.

Step-by-step strategies for dog leash reactivity training

There is no single “quick fix” for leash reactivity in dogs. Progress comes from layering small, consistent steps that help your dog feel safe and give them the skills to respond calmly.

1. Management first

Before training even begins, we set the stage for success. A well-fitted harness makes walks more comfortable and avoids pain-based tools that add stress. Guardians can also choose calmer walking routes, avoid high-traffic “hot spots,” and prevent habits like window guarding at home. The fewer chances a dog has to rehearse reactivity, the faster new behaviours can take hold.

2. Control distance

Every reactive dog has a threshold, the point where they go from noticing to exploding. Training works best just below that threshold. At this safe distance, your dog can see the trigger, stay calm, and be rewarded for the right response. Over time, that comfort zone gets closer as the dog learns new skills.

3. “Look at That”

The Look at That game teaches your dog that calmly noticing a trigger is a good thing. Each time they glance at another dog, person, or object and you reward them, you build a new habit. Instead of reacting, your dog learns to check in with you and expect something positive.

4. “Find It”

Scattering treats on the ground redirects a dog’s focus and encourages sniffing. This simple Find It game lowers arousal and shifts the brain from high alert into foraging mode. Sniffing is both calming and rewarding, making it an excellent tool in the middle of a walk.

5. Sniffing and decompression walks

Not every walk needs to be a training session. Slow, sniff-heavy walks let dogs reset their nervous system. Exploring at their own pace, following scents, and moving through a quiet environment all help lower stress. These decompression walks are as important as structured training because they give dogs the chance to relax and process.

6. Parallel walks

One of the safest ways to practice calm exposure is walking parallel to another dog at a comfortable distance. Dogs learn that being near another dog does not mean pressure to greet. Over time, the distance can close naturally as the dog’s comfort grows.

7. Behaviour Adjustment Training (BAT)

BAT, developed by Grisha Stewart, uses a long leash to give dogs more freedom to make choices. They can disengage, explore, or choose a calmer path without being pulled along. This method builds confidence by letting the dog practice self-regulation in real situations. Because it relies heavily on timing and reading body language, BAT is best guided by a trainer who understands the technique.

8. Pattern games and predictability

Games like 1-2-3 walking or “Up/Down” create a rhythm the dog can rely on. Impulse control games, such as waiting politely at a door or practicing “leave it,” help build frustration tolerance. Structure and predictability reduce chaos, which makes it easier for dogs to stay calm.

9. Gradual progression

Reactivity training is a marathon, not a sprint. Success comes from reducing distance slowly, step by step, as the dog shows they are ready. Rushing into harder situations too soon leads to setbacks. When training is paced correctly, each win builds confidence and lays the groundwork for the next step.

Real-life example: Charlie

Charlie is a 1-year-old poodle mix who spent much of his early life in a crate before being rescued by his guardians. Like many socially sensitive dogs, he shows the classic signs of leash reactivity: barking, growling, and lunging at both people and dogs. We do not know whether this behaviour comes more from a lack of socialization or from specific negative experiences, and the truth is that we may never know for sure. What we can say with confidence is that progress is possible, even when the starting point is unclear.

When Charlie first began training, he was afraid of almost everything on the street and in the park. Objects as ordinary as recycling bins, bushes, the netting on a soccer goal, or the flowing water in the park’s large water feature were enough to stop him in his tracks. He met the world with worry rather than curiosity. Now, after consistent work, he explores and sniffs with excitement, treating these same objects as part of his environment instead of threats.

His reactivity to people and dogs has also improved. The distances that once set him off have slowly shrunk, and when he does react, he recovers more quickly and can return to calm exploration. Instead of staying stuck in a heightened state, he is learning to shift back into more relaxed behaviour.

Charlie’s training plan is layered and purposeful. Enriched walks lower his stress. Counterconditioning and games like Look at That and Find It build positive associations. Impulse control exercises strengthen his ability to pause and think. Behaviour Adjustment Training (BAT) with a long leash gives him the freedom to make calmer choices in real situations. Together, these strategies build resilience, confidence, and coping skills.

As with many socially sensitive dogs, consistency is key. When everyone in a household uses the same approach, progress comes faster and feels smoother. Every small step forward matters. Charlie’s journey is a reminder that even when timelines are uncertain, meaningful change is always possible with patience, practice, and the right support.

When to seek professional help

Many guardians can make progress on their own with patience and practice, but some socially sensitive dogs need extra guidance. Seeking professional help is not a sign of failure, it is a smart step that gives your dog the best chance to succeed.

Professional support is especially important if:

- Your dog’s reactions put people or other dogs at risk

- Triggers are frequent and unavoidable in your environment

- Progress has stalled despite consistent practice

A qualified trainer or behaviour consultant can create safe setups, coach you on timing, and design a plan tailored to your dog. During a behaviour consult, you can expect a thorough history review, hands-on coaching, and a step-by-step strategy to follow at home. This structure helps take the guesswork out of training and ensures that progress is built on solid foundations.

To find a professional, look for someone who avoids dominance language and uses science-based methods.

Consistency also matters here. When all family members follow the same plan, results come faster and stress levels drop for everyone. Professional help is not just about teaching the dog, it is about building skills and confidence for guardians too.

Key takeaways

- Leash reactivity in dogs is common and usually comes from fear, frustration, or excitement.

- These dogs are not “bad,” they are socially sensitive and need help managing emotions.

- Punishment makes reactivity worse, while positive reinforcement builds confidence and trust.

- Training involves management, distance, reinforcement, and gradual exposure.

- Professional help can make all the difference for safety and steady progress.

Helping sensitive dogs thrive

Reactivity does not define your dog. They are not giving you a hard time, they are having a hard time. With patience, structure, and kind training methods, you can replace stressful walks with calmer, more connected ones.

If you are ready to start working through leash reactivity with guidance and support, book a behaviour consult with Belle & Bark today.

FAQ

What causes leash reactivity in dogs?

Reactivity often develops from fear, frustration, or over-excitement. Genetics, environment, and past experiences all play a role. Because the leash removes a dog’s ability to retreat or greet, their emotions can spill over into big reactions. By addressing emotions and building positive associations, these responses can be managed effectively.

Is leash reactivity in dogs the same as aggression?

Not usually. Most reactive dogs are not dangerous. They are socially sensitive and overwhelmed. That said, if left unaddressed, leash reactivity can escalate into aggression, which makes early training and management very important.

Can leash reactivity in dogs be cured?

It is better to think of it as managed, not cured. With consistent practice, dogs can learn calmer responses and enjoy better walks. Improvement may take weeks or months depending on the dog, but progress is always possible.

What equipment is best for a reactive dog?

A well-fitted harness gives gentle control without pain. A front-clip attachment can help redirect focus in tricky moments, but it should be used carefully and not as the main walking style. Overuse can strain the body, so it is best used as a management tool rather than the foundation of training.

How long does it take to see improvement in leash reactivity in dogs?

Progress depends on the dog, environment, and consistency. Some dogs improve in weeks, others in months. Recovery time between exposures is important so dogs can settle and process. The key is steady, humane practice at your dog’s pace.

Why is my dog reactive on leash but fine off leash?

When off leash, dogs have the option to create space or approach at their own speed. On leash, those options disappear. The restriction of movement adds frustration and stress, which can trigger reactions even in otherwise social dogs.

Can leash reactivity in dogs improve with age?

Dogs may settle as they mature, but reactivity rarely goes away without training. In some cases, it can worsen with age if not addressed. Training builds the skills your dog needs to handle situations more calmly.

What role does exercise play in reducing reactivity?

Appropriate exercise and mental enrichment lower overall stress levels. Dogs with outlets for their energy are less likely to carry frustration into walks. Activities like sniffing games, puzzle toys, or off-leash runs in safe areas all help reduce reactivity.

Should I feel embarrassed if my dog is reactive on leash?

It is normal to feel embarrassed when your dog barks or lunges, but you do not need to. Leash reactivity in dogs is one of the most common behaviour challenges. Your dog is not being “bad,” they are struggling with emotions. Ideally, others would give your dog space and understanding. Instead of focusing on embarrassment, remind yourself that you and your dog are learning together and every walk is an opportunity for progress.